Eli Lilly Stops Antibody Trial In Hospitalized Covid-19 Patients

(Posted on Wednesday, October 28, 2020)

KIEV, UKRAINE – 2018/11/21: In this photo illustration, the Eli Lilly and Company, Pharmaceutical company logo seen displayed on a smartphone. (Photo Illustration by Igor Golovniov/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

LIGHTROCKET VIA GETTY IMAGES

How do we understand the decision of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to halt the Eli Lilly antibody treatment trial? Is it a sign that monoclonal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, are ineffective?

The Lilly trial combined two drugs designed to interfere with SARS-CoV-2 infection: remdesivir, a drug that is intended to inhibit the viral RNA polymerase, and the Lilly drug, a monoclonal antibody that is meant to prevent the spread of the virus within an infected person. The trial participants were all hospitalized volunteers with serious complications from Covid-19. The intent of the trial was to speed up recovery and prevent further progression of the disease. I do not have information regarding the exact endpoints and whether or not they include prevention of progression, the need for intensive care, and death.

Why two drugs? The presumptive benefits of remdesivir make it a drug of choice for most patients with Covid-19. A recent WHO study of remdesivir conducted in many countries found that remdesivir had no effect on hospitalized patients—neither with respect to progression nor more serious disease and death. This finding did not surprise me, as the effects of the drug even at their best are described as weak to marginal. Nonetheless, most volunteers in a study of a new drug would rather receive remdesivir along with the new drug.

The NIH halted the trail because no effect on the hoped-for endpoints was observed. Patients on remdesivir fared as well (or as badly) as patients on the two-drug combination. In other words, the addition of the Lilly drug had no measurable effect. The preliminary report mentions no adverse events that occurred as a result of the two-drug combination.

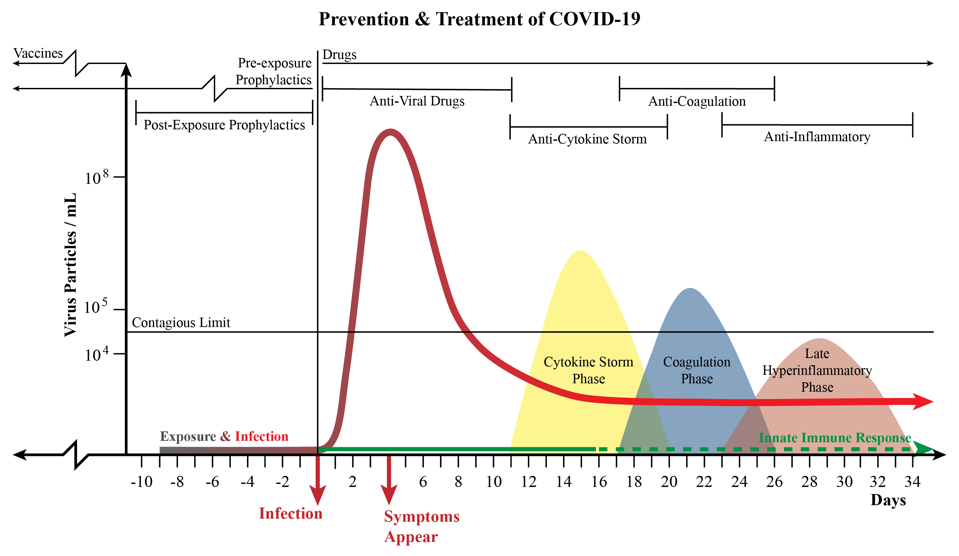

A chart that combines the phases of disease progression with information on treatments and prophylactics.

AUTHOR

Is this the end for the Lilly drug? Not at all. Drugs designed to stop virus replication should work, if they work at all, during the phase when the virus is most active. The figure above illustrates what we understand about SARS-CoV-2 growth in an infected person. There is a phase of a few days to a week following infection when virus growth is very slow. This is followed by a second phase when virus growth is rapid and the concentration of virus particles in nasal fluids, the lung, and the intestine is very high. That is followed by a third phase in which the growth of the virus is typically contained and reduced to nothing or near nothing. Antiviral drugs should work during the incubation phase and the phase of rapid growth, but not after the virus growth is controlled.

Most people infected with SARS-CoV-2 do not experience symptoms until after the peak of virus replication. Even then the symptoms may be mild and not require hospitalization. It is only later, after the virus is no longer replicating, that the most serious symptoms appear—those that require hospitalization. Treating hospitalized Covid-19 patients with antiviral drugs designed to impede a virus that is no longer replicating is the equivalent of the proverbial closing the barn door after the horse is gone.

When, then, should antiviral drugs be used? The answer is very early on in infection, or even before infection occurs. The obstacles that prevent us from using drugs early on in infection are related to how and who we test for infection. The people tested most frequently are those who have symptoms. By then the virus is already on the way out, and much of the damage the virus can do is already in progress. (There may be an exception for people who fail to make good interferon responses.)

There is a potential solution: frequent universal testing, whereby most people are tested every two to three days using tests that yield answers in 5 to 10 minutes. Such a testing regime, which I believe to be the surest way forward for contagion control, will identify those in the earliest stage of infection. Identification of an infected person should be followed by immediate treatment. Then and only then might antiviral drugs work, be they chemicals like remdesivir or monoclonal antibodies.

Antiviral drugs may also prevent infection, as is currently the case with HIV. Monoclonal antibodies are used to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in infants. Antimalarial drugs are used to prevent malaria infections. The caveat is that such drugs must undergo rigorous evaluations for safety, for they are intended to be used on healthy people who are not yet infected. The safety profiles of treatments for the healthy are much more stringent than those required to treat the ill.

I suspect that Lilly will go on to test their drug in those reporting mild symptoms. The first issue of that trial design is that only some of those with mild symptoms will be detected early enough for the drug to have an effect. An even greater issue is that the great majority of those with early cold-like symptoms—perhaps 80 percent or more—will recover from the cold and not progress to serious disease whether given a drug or not. Therefore, any possible therapeutic benefit will be diluted by the great majority of those that will not progress in any event. Such is the life of a drug developer.

The only way I see such trials as possible is the advent of very low cost, universally available rapid virus tests to identify those recently infected. Even then, the signal to noise ratio will be low.

In conclusion, this is not the end of the line for the Lilly drug, but it is the beginning of a very long and rough road for not just their drug, but any other Covid-19 antiviral.

Originally published on Forbes (October 28, 2020)