Protecting Indigenous Populations From Covid-19: The Australian Example

(Posted on Wednesday, May 5, 2021)

Covid-19 is likely to become endemic, yet through both public health measures and medical solutions we can control the virus. This is the second in a series of articles exploring examples of successful Covid-19 Control. Read part one here.

CANBERRA, AUSTRALIA – JULY 30: Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, Indigenous Australians Minister Ken Wyatt and CEO of the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation Pat Turner announce the targets for the Closing The Gap

GETTY IMAGES

Indigenous populations around the world are more likely to be infected by or die of Covid-19. In countries like Canada and Brazil and in the US, Indigenous people are dying at disparate rates to the general population. However there is one notable exception; Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders). Despite having a life expectancy around 8 years less than non-Indigenous populations and overall worse health outcomes, Indigenous Australians were six times less likely to contract Covid-19. Zero deaths and just 148 cases of coronavirus were reported for 800,000 Indigenous people across the country.

How did they achieve such a remarkable result? In contrast to previous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders health policies and interventions, the Australian government worked collaboratively with Indigenous communities. They provided flexible grant funding in March 2020 to 110 remote communities, allowing local Indigenous controlled health agencies to run a culturally aware response. As the scale of the pandemic became apparent, the government funding increased with $6.9 million invested in the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) and $123 million available over two financial years for targeted measures to support Indigenous businesses and communities to increase their responses to COVID-19.

Lines of communication between Aboriginal health organizations and government officials had recently opened because of a plan to address a syphilis outbreak using local Indigenous health services. Australia’s chief medical officer at the time, Brendan Murphy, supported the approach, which helped smooth the way for a community-led approach to the coronavirus.

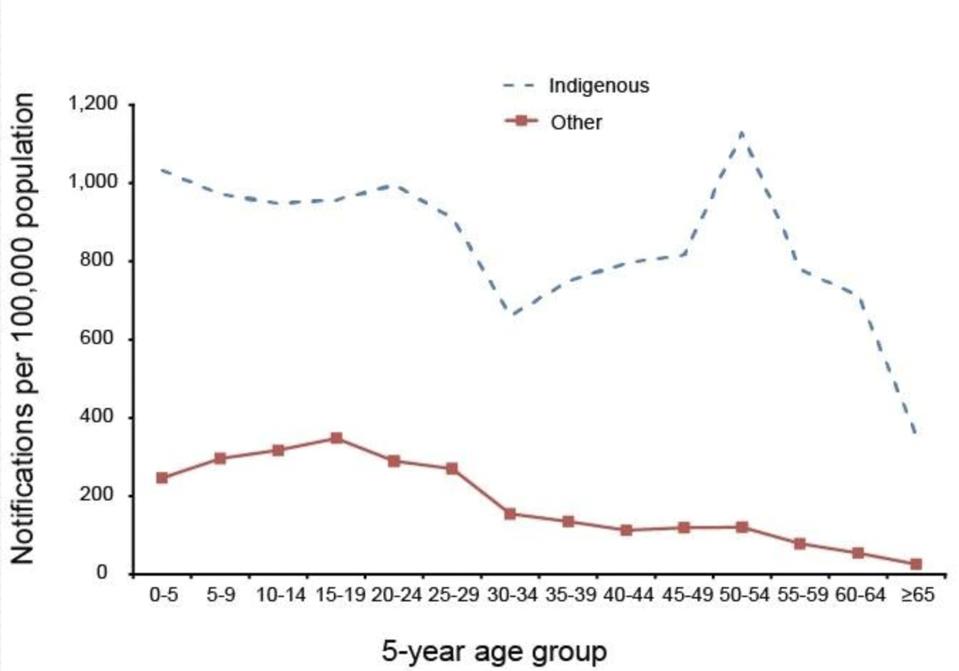

In 2009, during the H1N1 influenza pandemic, diagnosis rates, hospitalizations and intensive care unit admissions of Indigenous Australians occurred at five, eight and three times, respectively, the rates recorded among non‐Indigenous people. The chart below (Figure 1) demonstrates the vast disparities in H1N1 infections between indigenous and non-indigenous populations in Australia. These disparities were due to a number of factors; an already high burden of chronic diseases, longstanding inequity related to service provision and access to health care, and pervasive social and economic disadvantages.

Figure 1: H1N1 infections in Australia’s population in 2009.

AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

After the lessons of the H1N1 influenza pandemic, Aboriginal doctors and leaders were acutely aware of how vulnerable Indigenous populations would be to the Covid-19 virus and acted quickly. NACCHO established the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19 on March 5 2020, just three days after the first community transmission in Australia, co-chaired by the Federal Department of Health and the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation.

Remote communities began to close borders without waiting for official government permission, first the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands in remote South Australia, and then in Cape York and parts of Western Australia. The leaders of these communities decided to exercise sovereignty that had never been ceded. Meanwhile, Aboriginal doctors and leaders such as Pat Turner, chief executive of NACCHO began lobbying the Federal Government to officially close the borders to remote communities, citing grave concerns over the number of incoming flights from foreign countries that had rising levels of Covid-19.

Thankfully, the Federal government understood the stakes and the Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt, announced travel restrictions to remote communities under the Biosecurity Act on March 20, 2020. Border closures between all Australian states and territories were announced in the following weeks and months.

Recognizing the challenge in accessing testing in remote locations, the Australian Government invested $3.3 million to establish a rapid coronavirus testing program at 82 different sites in remote and rural Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Early messaging of the dangers of Covid-19 was critical for Indigenous communities according to Teela Reid, a Wiradjuri and Wailwan woman and lawyer. Public health messaging in Indigenous communities began in February 2020 (much earlier than in Australia’s general population) with a focus on keeping Elders safe.

Reid started a Facebook page for her community to share information about keeping elders safe. The local council soon connected to that page and devised a list of Elders who required medications and essential items delivered to them. Grassroots community organizing efforts continued to grow from there and occurred in remote communities across the country and in metropolitan areas where many Indigenous people live.

All major initiatives were run through the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organization. Communication and public health messaging was always clear, concise and culturally relevant using indigenous language and sometimes humor. Aboriginal health agencies also used Facebook, TikTok and Vimeo to spread messages including instructions on cough etiquette and hand hygiene, and conduct interviews with trusted health officials, translated into local languages. The Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia uploaded animated videos to Facebook to convey messaging on social distancing and emphasized maintaining regular check-ups using Telehealth services. Derbarl Yerrigan Health Service utilized Noongar Radio, an Aboriginal community station, to inform individuals on appropriate hygiene practices.

Dr. Mark Wenitong, the public health medical adviser at the Apunipima Cape York Health Council praised the swift response of Indigenous Communities in an Australian newspaper.

“This was the most proactive response I had seen from our mob” Mayors and communities in his own region, he said, had “utilized the public health evidence base better than any level of government in Australia”.

Fiona Stanley, an Australian public health expert hopes that the successful Indigenous controlled Covid-19 response will lead to more autonomy for communities in the future when tackling other health disparities.

“Indigenous people understand the context in which they are living, everyone knows where those elders were. Local services know who they are, and where they are, and can immediately create the best preventative strategies for them…when you give First Nations people this power it works every time.” Stanley told an Australian radio station during an interview.

“It was supposed to be a disaster, but because they acted so responsibly, it was a model of how to prevent an epidemic in a high-risk population. It just shows what happens when Aboriginal leadership is listened to.”

Pat Turner, CEO of NACCHO echoed these sentiments in a speech made in December 2020, “We know control, self-determination and community empowerment directed by First Nations peoples will work. Nothing else will deliver the outcomes we deserve.”

However, Australia’s Indigenous controlled response to Covid-19 is not only a blueprint for successful Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health care but also for successful Indigenous healthcare around the world.

Australia does not have a strong record on Indigenous relations and community engagement. Reconciliation for atrocious policies such as the Stolen Generation remains unresolved. Nor did Australia have a prior history of Indigenous controlled health responses. Yet the gravity of the pandemic forced them to reform their health systems and listen and give agency to Indigenous voices. Countries around the world can and must do the same or the consequences will be devastating.

Read the full article on Forbes

Originally published on Forbes on May 5, 2021