Getting a Grip on Influenza: The Pursuit of a Universal Vaccine (Part 2)

(Posted on Monday, August 22, 2022)

Taiwan researchers sort through eggs used for the cultivation of swine flu vaccine, in a plant in … [+] AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

This is a short series about a recent breakthrough on the road to developing a much sought-after broadly neutralizing vaccine against all influenza A viruses. If successful, it may act as a precursor to a truly universal flu vaccine, one that protects against all types, subtypes, and lineages of the virus. The breakthrough may also provide a blueprint for developing a Covid-19 vaccine that retains its efficacy in the face of new variants.

In the first part of this series, I gave a brief overview of the history and nature of influenza viruses, including why it has been so difficult to develop successful vaccines. The next few articles discuss some of the attempts that have been made to overcome these challenges, including their shortcomings. And in the last installments, I will offer a detailed analysis of the latest —and most promising— advances in the field.

The Seasonal Approach

Picking up where we left off in the previous article, any successful influenza vaccine has to account for the ability of influenza viruses to mutate. Genetic mutations to vital proteins can lead to antigenic variation — changes to parts of the virus that our immune system relies on to stimulate its “memory”. Although various different parts of the virus serve as antigens, the surface proteins that help it enter and exit host cells are some of the most important. Changes to these proteins can prevent our antibodies from recognizing the virus, rendering them unable to block its spread. Antigenic variation is responsible for influenza reinfections, leading to seasonal flu outbreaks.

In an attempt to circumvent the issue of antigenic variation, vaccine manufacturers update the flu shot each year based on the latest circulating influenza strains. The idea is to expose our immune system to the antigens it is most likely to encounter during flu season, helping it to build up its antigen-specific defenses in advance — once our immune system has built up its memory, it can jump into action straight away should we become infected.

Which influenza strains ultimately get used to make the yearly flu shot is decided on the basis of data collected throughout the year by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). This surveillance and response system is made up of roughly 150 different laboratories spread across the globe, each of which gathers thousands of influenza samples from sick patients. The most prevalent viral strains are then shared with five WHO Collaborating Centers for Influenza, which perform further analysis. Two times a year —once in preparation for flu season in the Northern Hemisphere, and another in preparation for flu season in the Southern Hemisphere— Directors of the WHO Collaborating Centers, Essential Regulatory Laboratories, and representatives of a few of the smaller national laboratories come together to: “review the results of surveillance, laboratory, and clinical studies, and the availability of flu vaccine viruses and make recommendations on the composition of flu vaccines.” Once the WHO vaccine composition committee has made its recommendations, each country makes a final decision on which viruses they will choose to use in their flu vaccines.

In the United States, all influenza vaccines are “quadrivalent”, meaning they contain four different influenza viruses. This is done to broaden protection against the various influenza subtypes and lineages known to drive seasonal outbreaks: influenza A (H1N1), influenza A (H3N2), influenza B/Victoria, and influenza B/Yamagata. Quadrivalent vaccines will also protect against any other influenza viruses that are antigenically similar.

Although this may seem like a relatively reliable process, there is one glaring drawback to the seasonal vaccination approach: vaccines produced in this way are nowhere near as effective as we might hope. At best, they protect 60% of people from illness, but this number can, and often does, drop much lower. For the influenza A (H3N2) subtype, vaccine effectiveness hovers around 33%. Of course, any protection is better than no protection, but it is still suboptimal— remember, these numbers represent best case scenarios, years where the viruses selected for use in vaccines are well matched to those that actually end up circulating during the flu season. So, where are things going wrong?

Missing the Target: Egg-based Vaccines

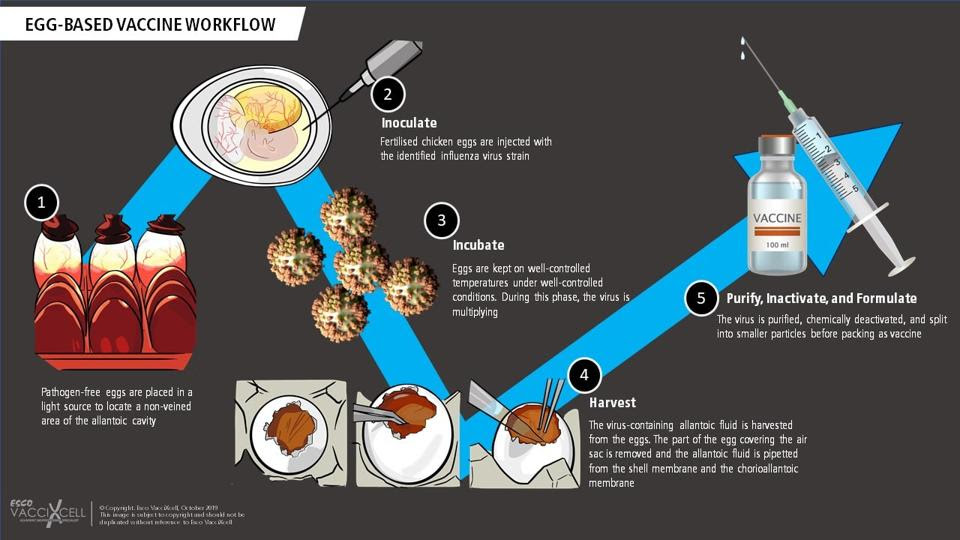

Selection of candidate vaccine viruses (CVVs) is only one part of the equation, growing them is another. This is no simple feat considering they need to be available in bulk, enough to make millions of vaccines. For the past 70 years, the majority of manufacturers have turned to chicken eggs in order to achieve the necessary growth (Figure 1). The candidate vaccine viruses are injected into fertilized hen’s eggs and left to incubate for a few days. During this period, the viruses are able to replicate. The fluid in the eggs is then extracted and the viruses are “killed” (inactivated). Finally, the antigen of choice —usually the hemagglutinin surface protein— is isolated from the killed viruses and purified, making it ready for use in vaccines. Even now, most flu vaccines continue to be egg-based.

FIGURE 1. An overview of the steps involved in producing egg-based vaccines. SOURCE: ESCO VACCIXCELL (HTTPS://ESCOVACCIXCELL.COM/

But there are two issues with this approach. First, growing the viruses in eggs is a fairly slow process. This means the selection of candidate vaccine viruses has to happen far in advance of flu season, to make sure manufacturers have enough time to produce the amounts needed. In the six to nine months it takes to grow and purify enough virus, the wild type influenza strains continue to mutate and change. If these changes impact the antigen, the wild type viruses may escape the immunity that the vaccines provide us, reducing their effectiveness. When this happens, the viruses are referred to as “escape mutants”.

A growing body of research

“Egg Substitutes”: New Ways of Growing Candidate Viruses

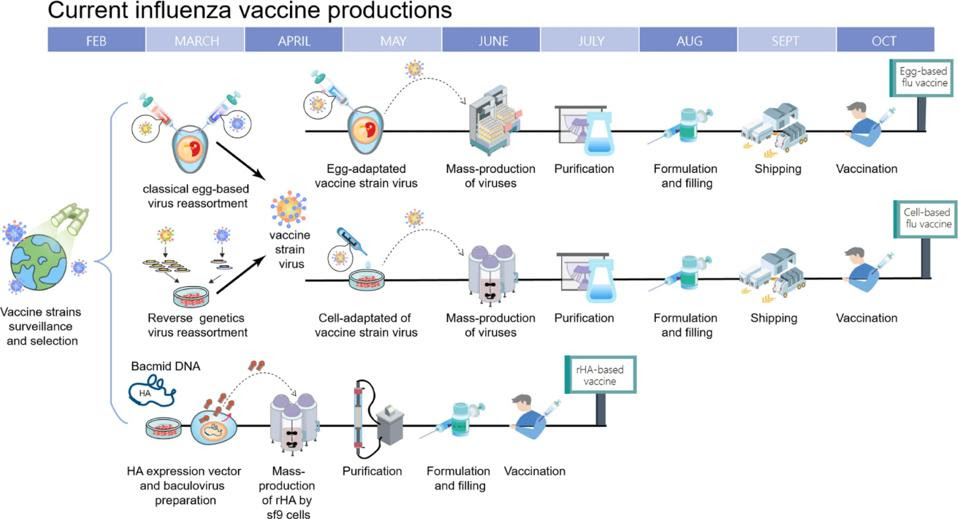

In response to these issues, manufacturers have tried to develop new production methods that avoid using chicken eggs to culture candidate viruses. This search has led to a cell-based approach and a recombinant approach (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Timeline of current influenza vaccine production methods. Schematic overview of egg-based, cell-based and protein-based (recombinant) influenza vaccine production. SOURCE: “BETTER INFLUENZA VACCINES: AN INDUSTRY PERSPECTIVE” CHEN ET AL. 2020

Cell-based vaccines are produced using candidate viruses grown in mammalian cells rather than chicken eggs. Aside from this, the manufacturing process between the two is virtually identical: candidate vaccine viruses are grown in mammalian cell cultures by the CDC, these are then handed over to private manufacturers who inoculate the viruses into mammalian cells, the viruses are left to replicate for a few days before being harvested, and finally, purified. Although approved in 2012, it wasn’t until this past 2021-2022 flu season that fully egg-free, cell-based vaccines were produced — previously, the initial production of candidate vaccine viruses by the CDC was still done using fertilized hen’s eggs, and only after being handed over to the private sector were the viruses mass-produced in mammalian cells.

Using the cell-based approach eliminates egg-adapted changes in candidate viruses, keeping the viruses as close as possible to the wild type influenza strains predicted to circulate during flu season. An added benefit of cell-based vaccines is that the production process can be scaled up more quickly; mammalian cells can be frozen in advance to ensure steady supply, which could prove especially useful during pandemic outbreaks.

In theory, the lack of egg-adapted changes should improve vaccine effectiveness. But what about in practice? Although there still hasn’t been enough research for a clear consensus to develop, initial findings suggest the difference in effectiveness is modest at best, and statistically insignificant at worst. This hints that egg-adapted changes might not play as important of a role as initially suspected; low vaccine efficacy can occur even when eggs are not used in the manufacturing process. That said, the 2021-2022 flu season marks the first time truly egg-free cell-based vaccines —in which all four viruses are derived entirely through cell-based methods— were used, so perhaps future research will yield different results. For now, things don’t look too promising.

Recombinant vaccines provide a third option, and manage to overcome a crucial issue faced by the other two options: the lengthy, tedious virus production process. Whereas egg- and cell-based vaccines depend on candidate virus samples, recombinant manufacturing skips this step. Instead, recombinant vaccines are made by isolating the gene that makes the hemagglutinin surface protein from a wild type influenza virus. Once isolated, this gene is combined with a different kind of virus, called baculovirus. The new virus is known as a “recombinant” baculovirus and it is used to ferry the gene that makes the hemagglutinin antigen into a host cell line. As soon as the gene enters the cells, they begin to mass produce the hemagglutinin antigen. The antigen can then be extracted and purified before being assembled into a vaccine.

Given that they are entirely egg-free and don’t require candidate virus samples, recombinant vaccines bypass the issue of egg-dependent changes. Due to the speed of production, there is also a decreased risk of escape mutants developing. As before, there is a paucity of comparative research, making it difficult to draw any firm conclusions, but early findings suggest recombinant vaccines may be more effective than traditional egg-based and cell-based vaccines, including improved antibody production.

Takeaway

Developing consistently protective influenza vaccines has proven difficult, with effectiveness frequently hovering somewhere between 40 and 60%. Too low, considering the threat posed by influenza.

A big part of the challenge is the mutability of the virus; it is constantly changing, making it hard for our immune system to keep up and retain useful “memories” of previous encounters. In response, public health agencies and scientists around the world develop new vaccines every year that prime our immune systems for the latest circulating strains. Sometimes scientists miss the mark with their predictions, in which case the circulating influenza strains do not match up with those in the vaccine, undermining vaccine effectiveness. At other times predictions are right on the money, but the vaccine production process impairs effectiveness either by being too slow and giving the wild type viruses time to mutate again, or because of mutations to the candidate vaccine strains during mass-production in chicken eggs.

Cell-based and recombinant vaccines aim to resolve the issues on the production side of things. The former by skipping the need for eggs, and by extension, the threat of egg-adapted changes. The latter by skipping the need for eggs as well as cutting down the time it takes to produce the vaccines, reducing the risk of escape mutants. Despite these advances, vaccine effectiveness has not yet seen the boost it needs.

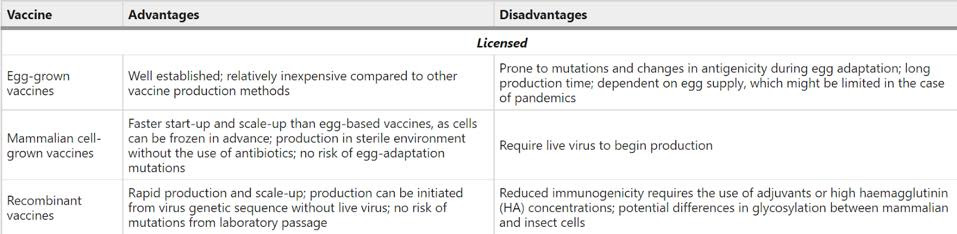

The below table gives a summary of the advantages and disadvantages associated with these three production processes.

FIGURE 3. Advantages and disadvantages of strategies for influenza virus vaccine production. SOURCE: “THE EVOLUTION OF SEASONAL INFLUENZA VIRUSES” PETROVA ET AL. 2017

The next article in this series will look at two additional technologies: intranasal vaccines and mRNA vaccines. Might they succeed where the more traditional strategies have wavered?