Two-Step Testing Could Slow Covid-19 Transmission Dramatically

(Posted on Monday, August 10, 2020)

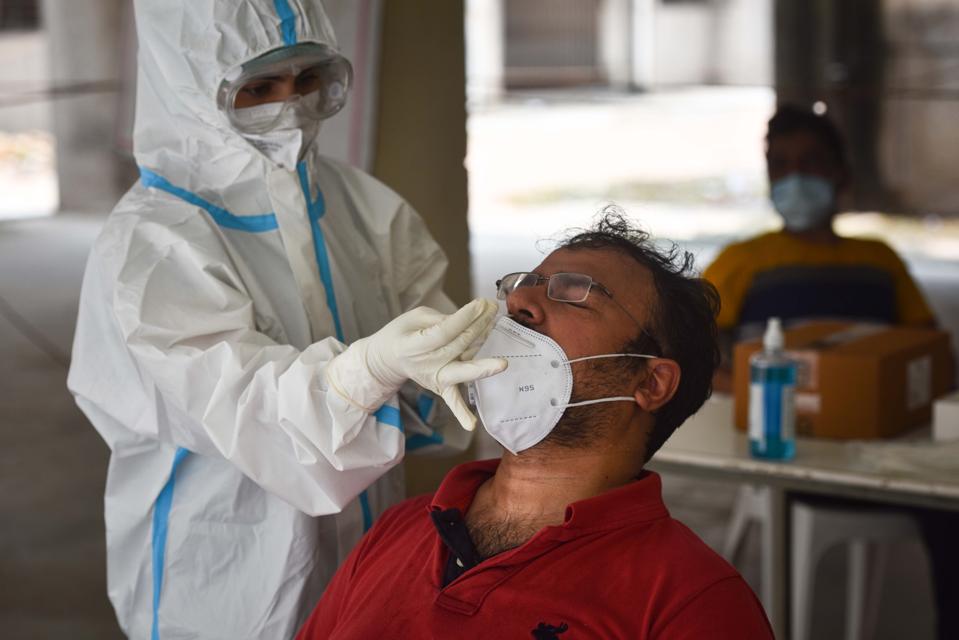

NEW DELHI, INDIA JULY 17: A health worker in PPE coveralls collects swab sample from a man for Covid-19 rapid antigen testing at a government dispensary, in Mehrauli, on July 17, 2020 in New Delhi, India. (Photo by Sanchit Khanna/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

HINDUSTAN TIMES VIA GETTY IMAGES

In the United States, testing for Covid-19 has become a persistent problem. For some without insurance, it is too costly. For others living in remote or underserved areas, too inaccessible. For us all, far too slow.

While some tests take only a few minutes to complete, most tests take much longer to deliver results. If the person awaiting results isn’t cautious, the time needed to process samples in a lab—anywhere from a few days to a few weeks—becomes time enough for the virus to spread far and wide.

The two-step method is not only a better way to test, but could potentially reduce transmission by 50 percent or more—and do so quickly.

Key advances in our ability to detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, make this new method possible. Tests were created early on that could measure the presence of viral RNA in any given sample using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which copies the sample a million times over to make traces of the virus easy to identify.

Of all the different kinds of tests available for Covid-19, PCR tests have proven to be the most accurate. They’re also the most expensive and time-consuming. Since processing a PCR test requires special machinery that can only be found in labs and research centers, the wait for results tends to drag out, especially in places where case counts are surging and capacity strained.

Another critical development was the creation of tests that detect SARS-CoV-2 by looking for viral proteins, or antigens, instead. Aptly called antigen tests, compared to the PCR tests these have the advantage of speed and convenience, in addition to being quick and easy to manufacture. A rapid antigen test authorized for use in India, the Pathocatch COVID-19 Antigen Rapid testing kit, reduces the wait time for results to as little as 30 minutes.

Like a pregnancy test, the rapid antigen test can potentially be used in the convenience and privacy of the home. But there is one major caveat to using antigen tests over PCR tests: they’re not nearly as accurate. Set loose in a sea of infections, the Pathocatch test, for instance, would only detect half.

The two-step testing method combines antigen tests together with PCR tests such that the strengths of both are exploited. The first step? Conduct widespread antigen tests using existing testing facilities. Those who test positive are assumed to be infected and instructed to self-isolate at home, where they can be monitored by local health authorities. Within 24 hours a contact tracing team interviews them about recent contacts who may have been infected, all of whom are brought in for testing as well.

Those who test negative proceed to the second step—the PCR test with a slower turnaround, but more accurate result. Until the PCR test results confirm or disprove their negative status, those who test negative the first time around must quarantine. Either way, the virus is stopped in its tracks.

In India, this two-step takedown is already underway. In Egypt, it was successfully used to screen 68 million Egyptians for hepatitis C, though with antibody tests instead of antigen tests as a first step. It could be implemented just as easily here, where the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already approved a rapid antigen test with a higher detection rate than the Pathocatch.

Testing is nothing short of essential to our ability to monitor and mitigate Covid-19, and in the United States this component has so far been lacking. Studies conducted across Spain and the United States have shown that for every case of Covid-19 confirmed using PCR tests, as many as five to 10 more go undetected. Confirmed cases in the United States currently exceed 4.5 million, which means tens of millions of infections may be eluding our grasp.

Even if the two-step testing method enables detection of just 50 percent of infected people, removing those 50 percent from circulation would slow the spread of Covid-19 dramatically. In other words, it is just the sort of sweeping intervention we need to make up for months of inefficiency and inaction. Why not start now?

Read original article on the Forbes website (published August 7, 2020)