Will Population (Herd) Immunity To Covid-19 Be Permanent Or Seasonal?

(Posted on Monday, February 1, 2021)

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – OCTOBER 31: People gather to celebrate Halloween in Times Square on October 31, 2020 in New York City. Many Halloween events have been canceled or adjusted with additional safety measures due to the ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19)

GETTY IMAGES

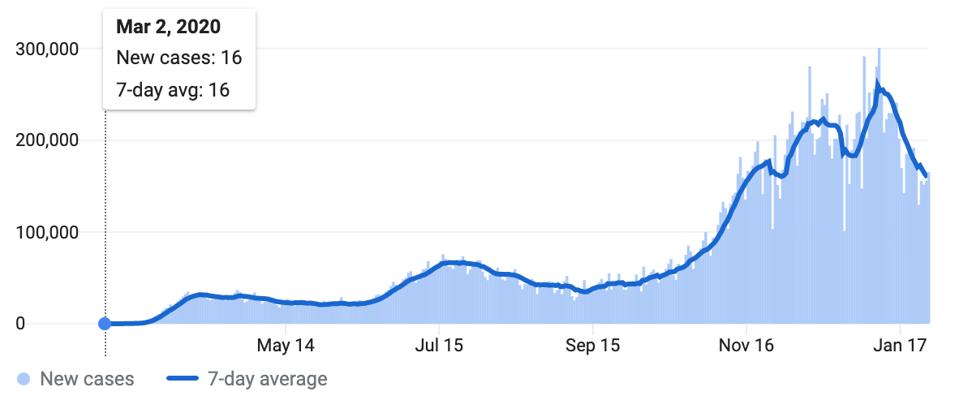

In just three weeks, the number of Covid-19 cases in the United States has plummeted by 35 percent. Death rates have yet to follow suit, but they have leveled out, with hospitalization rates on the decline, too. Given that the vaccine rollout is still proceeding slowly, the ebb is the glimmer of hope we need as we start to emerge from a long, dark winter. But is this really the light at the end of the tunnel, or just a period of calm before yet another storm?

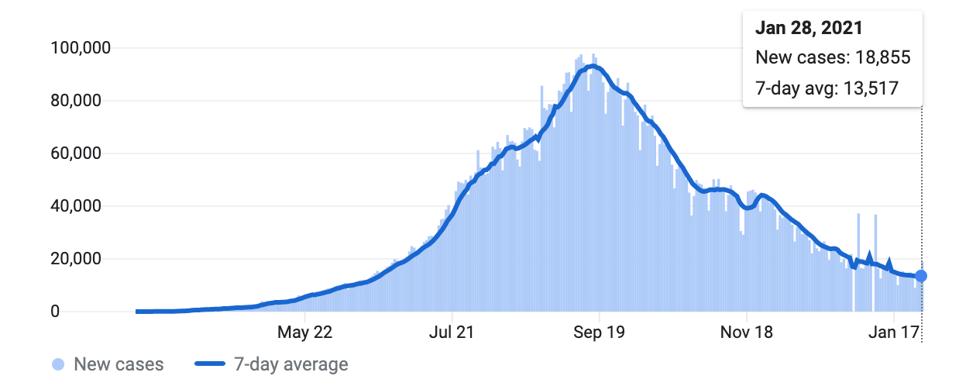

There are two possible expirations for the sudden decrease. Americans, whether chastened by the holiday surges or influenced by the new administration, may be embracing safety measures like mask-wearing and social distancing. But it could be that population immunity, also known as herd immunity, is on the horizon. While confirmed case counts hover around 26 million, a study recently published in JAMA suggests the actual number is likely four times as high, around 100 million. Between the 100 million Americans who have contracted the virus and the 24 million vaccinated so far, we may be in the early phase of a steady decline. Similarly, India reached peak infection in mid-September 2020, a time when an estimated one third of the population has been infected. Since then new cases have been on a steady decline from a high of 100,000 per day to roughly 12,000.

Chart of new Covid-19 cases in India. Each day shows new cases reported since the previous day.

JHU CSSE COVID-19 DATA HTTPS://GITHUB.COM/CSSEGISANDDATA/COVID-19

Chart of new Covid-19 cases in US. Each day shows new cases reported since the previous day.

JHU CSSE COVID-19 DATA HTTPS://GITHUB.COM/CSSEGISANDDATA/COVID-19By many estimates population immunity requires the majority of a population, around 60 to 70 percent, to have some level of immunity to the virus, offsetting its ability to move freely amongst naive hosts. Last summer, there was discussion that herd immunity—achieved not with vaccines, but through rampant, unchecked infection—might be a potential strategy for ending the pandemic. In the writings I published in response, I argued that this was not just a fallacy, but a recipe for further carnage and tragedy. With deaths in the US alone projected to surpass half a million by the end of February, this is regrettably now our reality.

But now that case counts are down and mass vaccinations underway, population immunity has re-entered the realm of possibility cast in a much different light. In today’s discussions, population immunity isn’t a strategy in and of itself, but a byproduct of unevenly implemented public health interventions and a year’s worth of transmission. Some now argue that infection of only third of the population is enough to spark a downward trend.

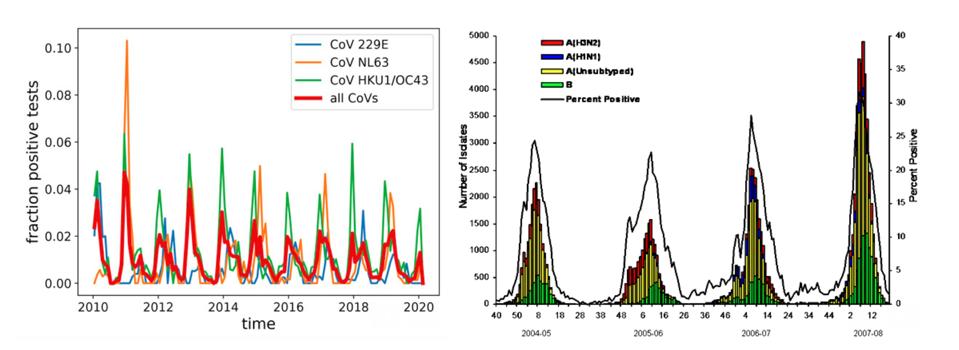

How might the pandemic play out over the next 11 months of 2021? Will the rate of infection drop and remain low, or will we face yet another wave of increased infections and deaths come late fall and early winter? In other words, are we entering a period of prolonged or of seasonal population immunity? In considering these two possibilities, I look to three factors: the immune response to infection, the history of coronaviruses that cause colds each winter, and the emergent shape-changing proclivities of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that calls SARS-CoV-2. Our collective experience with both cold viruses and influenza acquaints us all with the concept of immunity that lasts but a season.

Left: Seasonal variation of human coronaviruses in Stockholm, Sweden. Test results between 2010 and 2019. Right: Surveillance of seasonal influenza viruses from 2004 to 2008.

(1) POTENTIAL IMPACT OF SEASONAL FORCING ON A SARS-COV-2 PANDEMIC DOI: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.4414/SMW.2020.20224 PUBLICATION DATE: 16.03.2020 (2) CDC 2007-08 U.S. INFLUENZA SEASON SUMMARY HTTPS://WWW.CDC.GOV/FLU/WEEKLY/WEEKLYARCHIVES2007-2008/07-08SUMMARY.HTMInfection by SARS-CoV-2 triggers the production of IgM, IgA, and IgG antibodies that recognize the virus. IgM and IgA antibodies protect us against infection at our mucosal surfaces, but they are effervescent, lasting no more than a few weeks. IgG antibodies are thus the longest-acting of the three and carry the greatest potential for preventing infection, though reports of just how long neutralizing antibodies last in people infected by SARS-CoV-2 have so far been mixed. In some studies, including a recent one from China, neutralizing activity decreased as much as tenfold between February and October 2020. Overall both the magnitude and duration antibody response may depend upon the severity of the disease.

We all know influenza has the propensity to return to plague us each winter in a new guise, one that slips by our natural and vaccine-induced defenses. That is why we receive annual vaccines— to protect us from the latest influenza variants. The capacity of influenza to change seems unlimited. For as long as I can remember, each new winter is heralded by a new flu variant.

Until very recently the annual return of cold-causing coronaviruses was more mysterious, as these viruses were thought to be stable, with no significant variations reported. As it happens that is because no one looked until now. Surprise! Influenza now has a changing cousin. The one cold-causing coronavirus strain studied, known as 229E, not only changes, but evolves over time to evade the prevailing immune responses to its predecessors. The seasonal influenza’s winter peaks and those of the cold causing coronaviruses appear to be due to the same two factors, waning protective immunity and immune evasion.

It is this context that makes the recent discovery of new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus variants so troubling. The variants share several features of concern. They are more easily transmitted than their predecessors, more resistant to neutralization by the antibodies in the blood of patients infected with early strains of the virus (and in some cases to the antibodies in those immunized with anti-Covid-19 vaccines), and are found in more abundance in nasal secretions of those infected. Specifically, one recent study found that whereas most of the sera collected in October from 20 people infected in January was able to neutralize the original, so-called Wuhan strain, only two of the 20 inactivated B.1.351, the so-called South Africa strain. Meanwhile another study conducted in South Africa found definitive evidence that B.1.351 infects those who’ve recovered from prior infection by the original infecting variant. The South Africa variant is also far more resistant to the Novavax vaccine, evading both natural and vaccine induced immunity.

My conclusion is that we may very well face a renewed winter wave of Covid-19 this year, driven both by aging immunity and virus variation. We must heed the lessons of influenza, as well as those of other coronaviruses. What we may be entering now may be only a respite, best described as seasonal immunity.

We are not helpless. First and foremost, we must do all we can to eradicate Covid-19 as quickly and as thoroughly as possible within our respective borders. Today the US accounts for almost one quarter of all infections. We should beware not only imported variants but homegrown ones as well, some of which, like the California and Ohio strains, may have been spotted already. The current vaccines will speed us on our way. New vaccines adapted to the variants as they arise will also help. But I am not alone in warning that vaccines alone are not the entire solution.

We must also do what is needed to prevent transmission by following the guidance of our public health experts. Others have kept their countries free of Covid-19, save for intermittent imported outbreaks. Identification of those infected, followed by isolation of those infected and exposed, is critical. Today the US has fallen far short of this goal. Vaccines will make the job of eliminating Covid-19 easier, but cannot do it alone. Failing Covid-19 eradication, I fear we are in for another dark winter—perhaps not as dark as today, but one we all must do our best to avoid.

Originally published on Forbes (February 1, 2021)